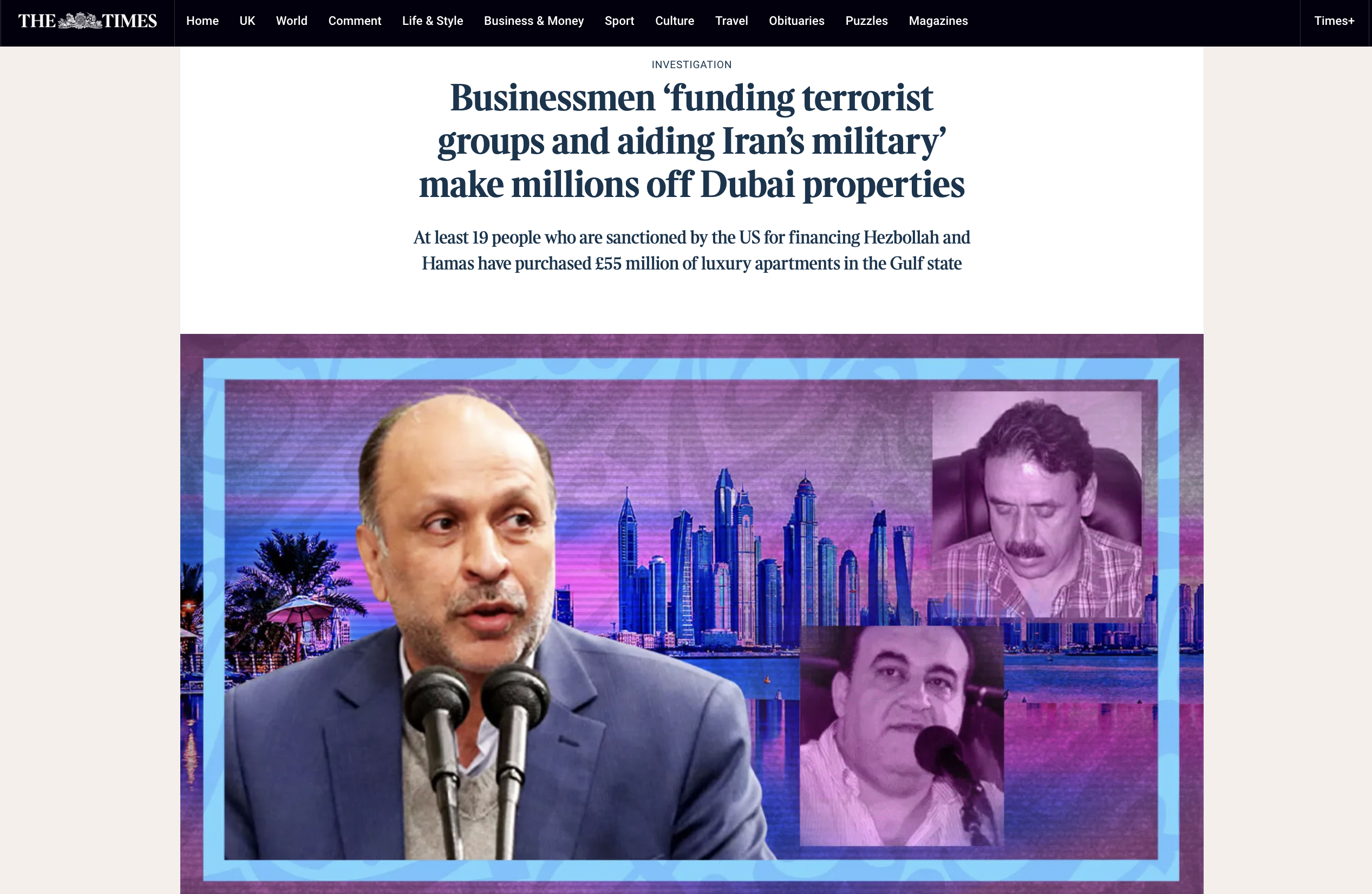

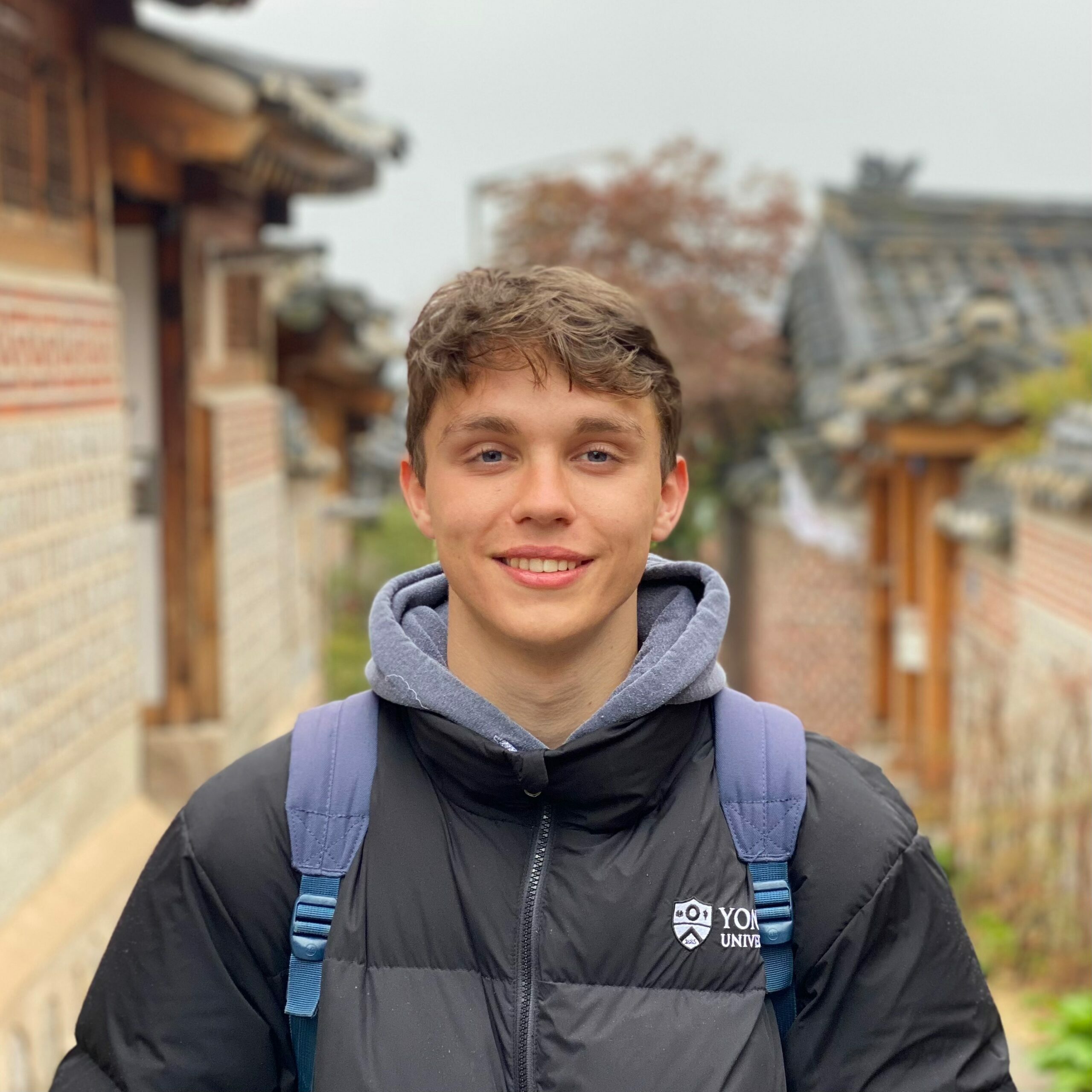

Criminals, oligarchs and crooked politicians, look away now. George Greenwood is at the heart of The Times’ investigations team, where he focuses on exposing financial crime, lobbying malpractice, and foreign influence.

In 2023, he was shortlisted for the European Press Prize in recognition of his work with the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) on how key Putin allies manage to evade Western sanctions. We spoke to George at the Student Publication Association National Conference 2024 about a day in the life of an investigative reporter, the importance of transparency in public life and how young journalists can begin to prowl their patch.

How would you describe your job on the investigations team?

I do a lot of this transparency work on UK government. I also do a lot of financial crime and a lot of stuff around Russia and China and how UK public authorities and businesses deal with them. I try to shed light on things that either shouldn’t be going on or are illegal. It’s that sort of traditional public interest journalism, really, but using slightly different techniques.

My boss, Paul Morgan-Bentley, is just one of the best in the country at undercover reporting. That’s not something I’m as good at. What I am good at is looking at spreadsheets, putting things together, finding the story, but then doing the ringing around and door-stepping people. So you get the leads from the data, but then you do all the traditional sleuthing on top of that to make it work. I think there aren’t enough people who are both proper old school hacks and coders and data experts and FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) lawyers. So for my job, I have to be a lawyer, a data analyst and a hack. It’s just a random coincidence of events that led me to develop that skillset.

Reporters need to focus on those hard skills and I think you can get really amazing stories by just having those scientific skills and legal skills, as well as just being able to ring someone up and have a conversation. In a way, in journalism [training], I wish they did focus on those hard skills. You have data courses, but just things like teaching you to do Excel properly, because a lot of news reporters won’t have that, but it opens up this world of possibility of stories if you can just do Excel competently.

What would an average day be like for you? Is it very dependent on whatever you’re working on, or do you have a routine?

So, I tend to have a routine which ramps up and down depending on what’s coming up. A normal day is that I probably get into the office at about 8am in the morning. I spend an hour going through my FOI appeals. You could just spend all your time doing this, but you have to be quite strict, only spend an hour or two a day on it. I’ll file my appeals, I’ll make my requests, I’ll go through my backlog to see if I’ve got anything back that’s interesting and then maybe make a note to write a memo for the news desk on it.

Then, probably, the rest of the day, nine to five, it will be working on the main project. So at the moment it’s this investigation about money laundering and it’ll be making the calls, looking through the cuts, doing the calculations, searching through databases, looking for material and talking to our lawyers about things going on, updating editors.

Then the rest of the time will be spent meeting sources, so that could be anything from a mate I know does something, to somebody who wants [to meet] in a cafe with no mobile phones. It’s a real variety and I think just going for coffee with people is really important because they may say they’ll say things in a less guarded way than on the phone, because they [know] that you know you’re not recording them.

I almost find that sometimes it’s good not to turn up with a notepad, because I think as soon as you get your notepad out, people seize up a bit. Not to say you don’t take one, but just don’t open it until you really need to write something down in it that you’re going to forget, because, if you’ve got a good enough memory, sometimes remembering the key facts is better in terms of what you get out of people.

How many FOIs do you currently have in?

Hmm. So I’ve got probably only about 15 or 20 live ones at the stage of they haven’t responded yet, but I think I’ve got about 32 live ICO [Information Commissioner’s Office] complaints, seven live first-tier tribunal cases and one live upper-tier tribunal case.